Liberal imagination tends to consider translations as an act of building between cultural bridges. But if the history of colonialism and all the nationalist hegemony has a lesson offered, the building bridge is not necessarily the underlines guarantee. The translation is an act of faith, and as someone who cannot produce new discourse only confirms the existing, a translator is a helpless number, even when their existence is at stake.

This helplessness is in front and the square in the first scene of Jasmila žbanić’s quo vadis aida?

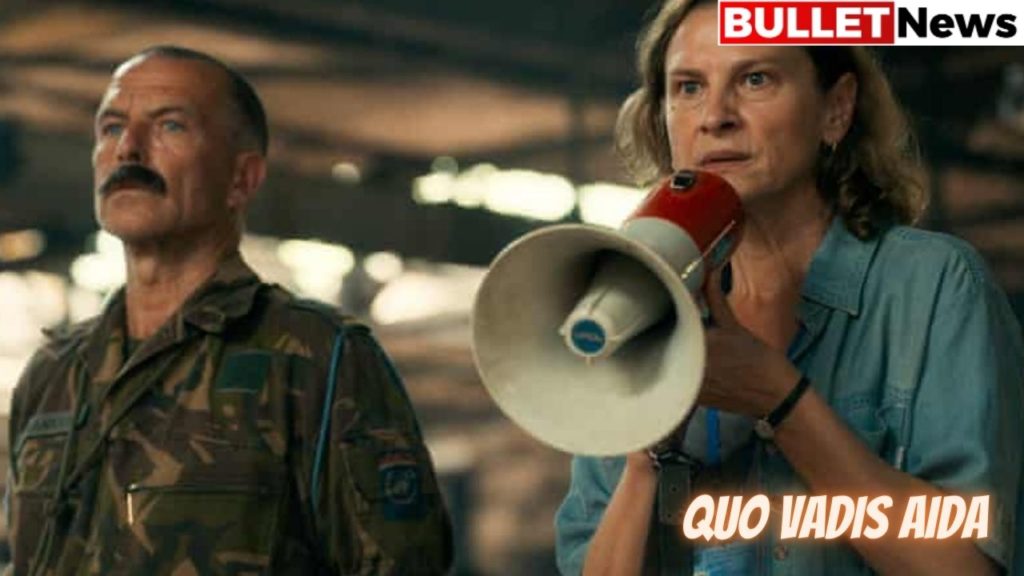

Sitting in the middle of the cloud of cigarette smoke, a tense translator but focused, Aida (Jasna đuričić), translates between a mere group of the civilians from Srebrenica, Bosnia, and UN peacekeeping unit. Which should be in a “safe area” which the United Nations protect. At the same time, blue berets assure them that the Organization of the North Atlantic Agreement (NATO) has their back.

As a camera pan back and forth between two camps:

The meditation denies the tension of the situation. The Aida translates words, but the critical part of the communication is successful without its intervention: up and falling pitches, the sound trembles, challenging, and denying handshake. Aida is found to be involved in the deadlock. But the emotional state has a small bearing on the negotiations’ tenor or the results. Hers are not for why but to facilitate a process. Even if it sends a group of people to specific deaths.

Quo Vadi dramatizes the days before Srebrenica’s massacre. Where more than eight thousand Bosniak Muslims are slaughtered. This weaves a factual account about how genocide is allowed to occur. With the story of the fiction told from the point of view of Aida. Several factors called to court: deep ethnophobia from the Serbian army, the cunning manipulation of General Mladić (Boris Isaković), which regulates the massacre, NATO indifference for whom Bosnias is only a pawn on the political chessboard, and the failure of the UN command to stand for mladić and capitulation Despicable to him.

All precise analysis will be formally not heavy for Aida characters, which bind this different perspective together. His unique position between Bosniak and UN forces helped the film never deviate too far from his own story. To save her husband and two of his sons. From the fate provided for members of his other community.

Part of the achievement of žbanić is how he managed:

To open a film from this narrow narrative perspective for more excellent political questions in a somewhat organic way. This tactic is not without a large enough restriction. With the hung mass that formed refugees in the UN camp. Marshaled refugees, instead, became a series of sketches that describe the injustice and violence they submitted – images that remember the recreation of Hollywood’s historical cruelty in their virtuosity troubling. There is no reference to anything for armed resistance by the Bosniak army or civilians is. Moreover, political comfort weakens the film’s argument.

But the actual human complexity came with the coda expanded film where Aida returned to Srebrenica after the war. In his class in schools are children of genocide victims and people from the perpetrators and supporters. Can Aida ever taught again, given that it was one of her former students who helped deport her husband and son

With the victims now, it is expected to put their past behind and become part. Of the same civil society as war criminals. The idea of truth and reconciliation of hollow rings. Performing together at one stage for school programs, ethnically diverse children looks fine. At least that, be the hope of Aida.